Passover in Piraeus: A Travelog

Bearing Witness with Afghan, Syrian and Yazidi Refugees, Greece, April 2016

This trip coincided with ancient Jewish calendar week of Passover (Hebrew: Pesakh,) marking the personal, collective and universal human arc towards liberation from oppression, displacement, yearning for refuge, and ultimately hope in the face of, and in lieu of, impermanence. It is also time for family gathering, warmth, and community — bearing witness to individuals and collectives experiencing a present day exodus in this particular week gave me a new meaning to the sacred holiday, and a new way to mark and practice it.

This travelog is an excerpted summary of six blog reports published in April 2016. For the complete unedited posts, see the links at the bottom.

Day 1: Arriving In Athens

[…] On the bus from Athens airport, standing space only, I looked at the scenario passing by. The old airport where recently some of the refugees were relocated to from city piers. At first I see nothing but abandoned hangers, tin roofs and bare runways, then colors streak by and I see them — yellows, reds, blues orbs.

At the apartment I catch up with other volunteers. Others left either on schedule or before planned. Some where burned out, some were frustrated with the unexpected results of doing good — one person brought toys to give to kids only to have them brawl among them for who gets what.

I hear that camp 2 has already been evacuated by the army, and that the situation there is changing daily. There are only two translators among the refugees, one of whom is an eight year old Afghan boy.

Day 2: Passover Eve with a Yazidi Family

We make it across to the port. Massive freighters and island shuttle dock and load. Port E2, a bustling tent camp last week, is now clear. We walk further and arrive at camp E1.5, situated between port E2 and E1.

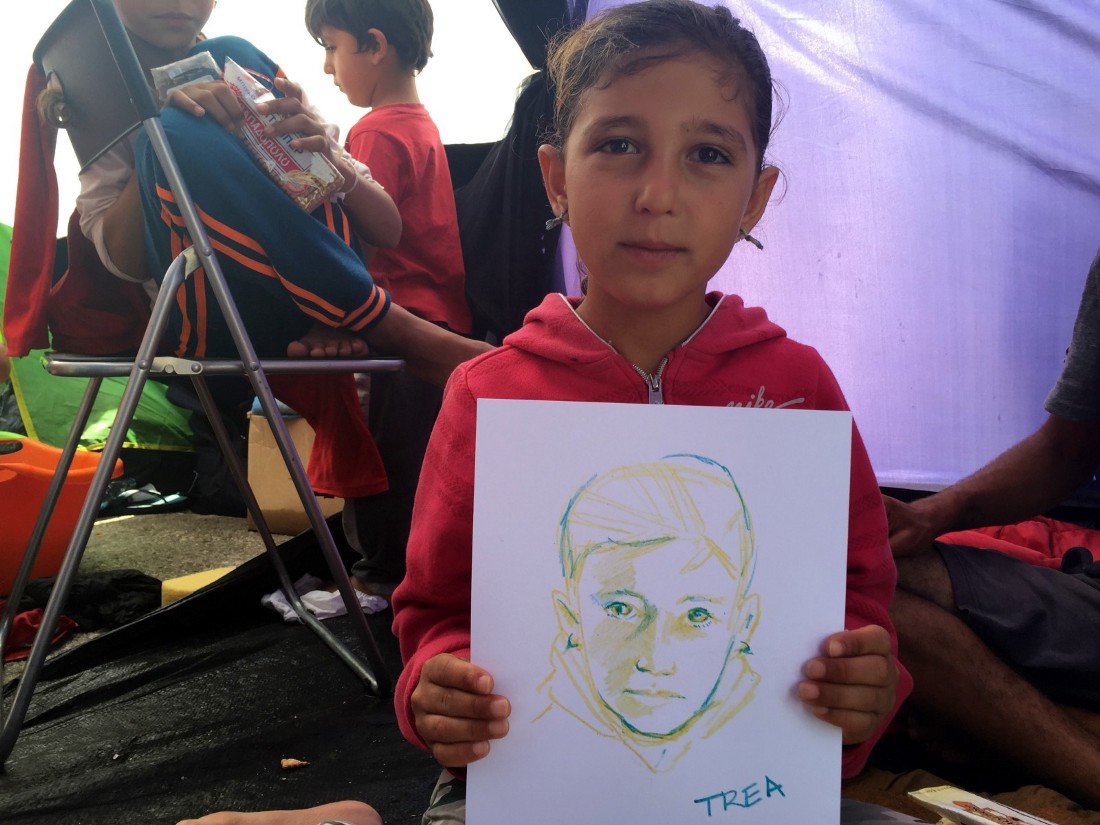

[…] I follow Maher to two 2-person tents joined. I take off my Nike shoes and place them by the plastic flip-flops at the entrance. My mind flashes to my visits to Japan. The universality of traits of one’s home. Dignity. Hospitality. Warmth. I return to Piraeus and lower my head and find inside a middle-aged woman scrubs a young naked young boy in a tub, and two girls sitting on plastic milk crates. Big smiles, curious eyes. Bags of clothes behind me. I smile at the kids and take out the packages of crayons and paper. I set it out on the blanket and encourage them to draw. They are embarrassed first and they jump in.

I draw his mother Bse, his sister Amanda’s braid, Trea’s blue threads for earrings, his brother Samil’s round nose. While I draw a curious teenage cousin, Maher rolls a cigarette and offers it to me. He sends Samil away and a moment later he returns with a lighter. We light the cigarette and the cousin takes off to return the lighter. I take note. They need a lighter. Amanda hands me over a brand new pencil. A gift. They offered me crackers, ‘Naniq’ in Kurdish, and I answer ‘Mamnoon’, thank you. They insist I take a bottle of water, “We have more.”

Taking water and food from refugees? I recall that I am not here to help. I am not here to volunteer. I am here to invoke the mind of not-knowing, not knowing what help is, not knowing what connection is, and to let each moment be an opportunity to experience curiosity and connection.

I take the water. I receive the pencil. I smoke the rolled cigarette. Mamnoon.

Maher tells me he has been two months at this camp, and stayed one month in Turkia (Turkey) on their way. I ask him how Turkia was and he says quietly “Very bad. Very bad.” Their family is Yazidi from Iraq, one of several hundreds other Yazidi here. I see Samil struggle to open a plastic case of a flashlight with his teeth. “Knife?” I ask. Maher says “No knife, dangerous. Yazidi never fight.” He says brawls happen in the camp over trifles, but never among the Yazidi. I put ‘scissors’ along with the lighter on my mental shopping note. I ask if they need anything and Maher says nothing with his chin down. He reaches to a backpack and takes out a plastic case of photos and shows me a creased picture of clergy in procession. “Yazidi.” He says. He then takes out several photos of another man, “Father. Died in Iraq.” I take a moment to take in this family of eight before me, their mother, this tent, this camp, the whole thing. “May I draw a portrait of him?” He nods and they all watch in silence as their father’s face rises in color from the page. Another cousin enters the tent and Maher says quietly, “Saedow” — father’s name. Maher receives the portrait and shows it to his mother.

I use Amanda’s pencil to draw Maher. The act of drawing, spending time in silence, the little expression of discomfort when intimacy gets a bit too close for comfort. There is a tenderness that settles, and tiredness revealed. The act of drawing shaves off inner and interpersonal walls , and part of me is concerned with facilitating his actual emotional contact with the unimaginable pain that this man holds, a glimpse of which I see when he takes quick peeks at his father’s portrait. This part of me thinks this is not time to ‘process’ or grieve, this time is for truckin’, surviving. I take a breath. I recall that I don’t know what ‘this’ time ‘is’. I don’t know. I can only drop what I think should or should not happen, bear witness to what has already arisen, and trust.

The family’s father

Maher offers me another cigarette, this one Iraqi, as if it’s the best thing in the world. He sends his cousin away again and he returns with a different lighter. We smoke in silence. Ashes fall from my cigarette on the carpet, making a small hole. Maher says, “don’t worry.”

I say Mamnoon. I leave the crayons, paper, and a handful of plastic sleeves with the family and step out with Maher. We walk quietly away from the tent. Then Maher lists quietly:

A mirror, two sets of T-shirts and pants, a knife, a pair of scissors, lighters.

I jot down the list to bring tomorrow. Maher spells his full family name for me to find him on Facebook. we hug and part.

I walk towards the water, towards the cadence of coming and going of the waves, past a young covered woman with wailing snotty-nosed child; towards the water; past the line of people standing in line to the storehouse where clothes are distributed; past the food line; towards the water, I hear the Greek volunteer leader shouting at a refugee walking away with a box of food; I walk towards the water; Towards the soft lapping of the waves, the chiming of the freighters bells echoing away from shore. I think of the ripples of people, of stories, of beginnings and endings, of the constant flow and the particular of each point on it on those circles. I think of the ripples our stories send out on the surface of our planet, from Pine Ridge, from Auschwitz/Birkenau, from Sarajevo, from Jerusalem and Bethlehem. This evening of Passover I hear the prayer of Bounty from the Jewish Haggadah sung in Hebrew with my family in Israel, the Four-Direction Prayer sung in Lakota in Pine Ridge, Sufi Illahis in Bosnia, same song in different languages — and right here in the ports of Piraeus I hear Sheehan’s Kurdish song. Mamnoon.

Amanda’s drawing of me

Day 3: Bearing witness at the camp, see link at bottom

Day 4: On separation of families

We emerged from the tunnel leading across the road. To our right were two accordion busses and dozens of more families some carrying three four backpacks at a time, large belonging wrapped in blankets, children in strollers or laying on hips of bags, a young woman with stark eyes in a wheelchair.

This was Skaramagas (accent on ga), a new state-run camp to house up to 6,000 individuals. Through the NGO grapevine we heard of good living conditions and of bad food poisonings.

[…] Everyone was moving towards a tree halfway to the gate where the Greek police checked theirs documents and let family by family move towards the gate where they were checked yet again. I helped Muhammad’s family move their belonging towards the entrance. There was a mild disorder and I notice the cool with which the Greek police officers show. I told the captain we were volunteers “Go in, go out.” And the captain let us through the first check towards the gate. An officer counts again, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight and looks at the paper again. He sees one young man and thought he was ‘nine’ ordering him to step back. Another young man from that family pointed again at his family members. “One two three four five six seven eight.” My mind flashed on the three years I was in the Israeli military police investigation department, and how the incidents of police violence I witnessed or investigated, started. I was concerned of the rising tension. This time the count was correct and the family moved towards the gate. This time the four of us witness/volunteers were not allowed in but we got a good glimpse of the inside : rows of rows of new white metal containers, I didn’t see any power lines, I saw some covered searchlights, trucks. We moved back.

As the people advanced, some were sent out of line because even though their family’s documents were stamped, their own documents weren’t. I noticed that those were all young men. I ask the police what these men should do and they say go back to Piraeus. I wonder how.

Periodically we notice men walk in and out of the gate, seems like they were free to do so. The officer checks their papers and let them out. Then said officer calls them back and points to the ground. One dropped a fresh cigarette. I smile with relief and care. Others come out, pushing baby carts, to bring in the rest of the belongings left from the location of the busses. A wheel chair rolls by with a disabled boy who, I suspect from the shape of his body, has cerebral palsy.

Masoud, whose English and spirit were best, showed us his papers and points where the red block stamp was missing. He was Afghan from a town 1,400KM west of Kabul who fled the Taliban. He had spent one month in Mitilin, another Greek refugee camp. He found himself on my phone’s Facebook and click ‘+friend.’

I took the phone and enter Facebook’s Immigrant and Refugee Support Group in Athens, a bustling online hub for resources and connections between volunteers and groups we use to get updated. I typed, “Does anyone know why some weren’t stamped? Where can one get stamped?” I described the situation. I clicked Post.

A football arched over the fence from the inside and lands in a soggy green creek by the camp. Shouts of excitement — A few of the men swung on swings outside the camp. One of them was so stunningly beautiful with his slanted Mongolian eyes and sharp sculpted face I found myself staring into his face.

An answer on the Facebook page Arrived. “Anyone who got on the bus should be let in.” Another answer appears with a phone number of a refugee coordinator. I call. They are on their way.

The scene we witnessed earlier reminds me of the testimonies and photos of the Nazi transports, I think of my Polish and Hungarian great grandparents unloading from a train at the platform in the center of Birkenau, the officers, the families, the selections, the confusion, the uncertainty. I think of self-internment in my own mind, when stimulated by anger I segregate a vulnerable feeling, a hurt, a pain, fear, not wanting to acknowledge it’s a living part of the large, diverse, vibrant, creative community that was ‘me’.

I think of intention. Auschwitz, Gaza, Srebrenica. All had fences, watchtowers, and guards. But they were all different, and created with different intentions. How the same objects, living containers, a fence, a guard, a document in itself have no value — it is my own intention in the mind and heart that determines how I will close a gate, that requests a document with a certain tone, that stamps it with acknowledgment of the quivering hand that holds it.

I think of the Greek officer, the intention in his heart, letting not knowing permeate my body. It was I who now walks inside the fence, five Afghans follow my steps. I feel thirsty. Nervous. I want to do a good job, to contribute; I feel afraid and want to be seen as person, but I was only taught be tough.

Compassion is a fancy words that means many things to many people. It works for me to imagine myself in another shoes, and imagine what they feel and what they value, I just feel connected and spacious when I do that. And really let that in. It all rests on not-knowing, being curious, letting go of judgments or preconceptions and stay with the felt unspoken sense of the experience of another, the feeling, energies, values, needs. I breathe into the richness of the shard of fabric of experience, myself, the guard, the men walking behind him, the stunning Afghani man on the swing, the little boy with the wrangled hands, my newborn newphew in Germany.

Two more buses arrive. The scene repeated. A hundred more people disembarked.

Tension rose. Captain shouted. Supply trucks arrived. I helped move bags from the road.

Among the arrivals was the beautiful grey-haired woman who received the make-up kits on the first day. I saw Milad, the Afghan whose mother survived a heart attack en route from Turkey. Swagger gone. Vulnerable eyes. His mother besides him, long face under a blue shawl. He told me of a phone call. Her mother, his grandmother, had just died back in Afghanistan. We hug.

I watched him and his mother enter the line.

I check my phone. Masoud accepted my Facebook friend’s request. He messaged, “Got in no stamp.”

I reply, thumbs-up.

Day 5: On volunteering with children, see link at bottom

Day 6: Final reflection & engaging an astronaut’s perspective

Acruise shuttle ship capsized the day I left Greece, and no one seemed surprised.

I walked into the center of camp E1.5 and ran into Masoud. “what the hell you doing here?” I asked him — I saw him get into Skarmagas two days before. “No stamp yet.” He answered. He was wearing the same cloths.

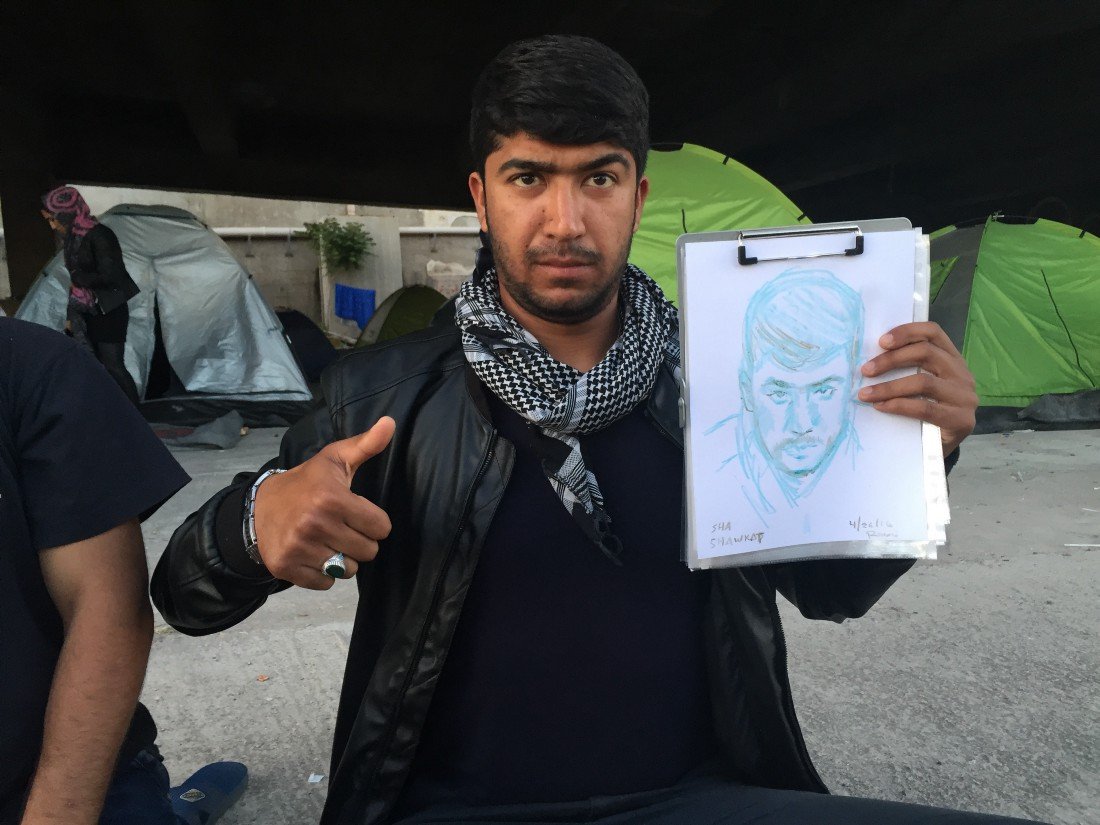

I sat down on a grey wool blanket that reminded me of my army days and skin rashes and joined his buddies for a game of cards. It took me a few rounds to understand the rules. Shawkat asked where I am from and when I said Israel he flexed his arms and said “Netanyahu — strong president! Israel — strong army!”. I asked him if he was a soldier himself. He said yes, in the Afghan army. I gave him my wide rim hat and called him Indiana Jones. Everyone laughed and I was surprised they knew to whom I referred.

I watched six grown men converse, tease and laugh with each other and felt the fun and connection between them without knowing one word in Kurdish. It was all in their glances, the sarcastic air-kisses, the way their voices went up then down, the dramatic pauses and the universal brotherly brawls.

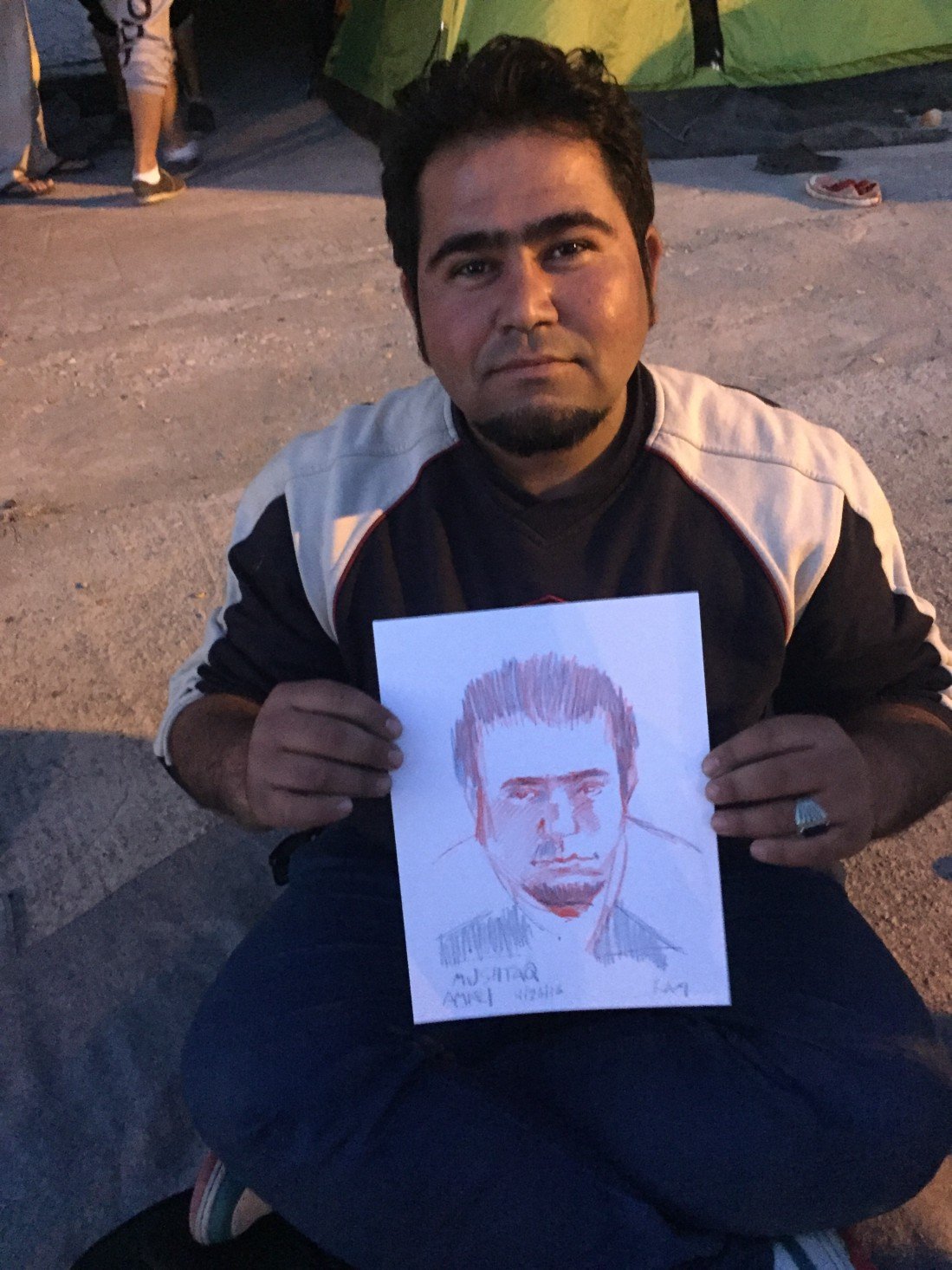

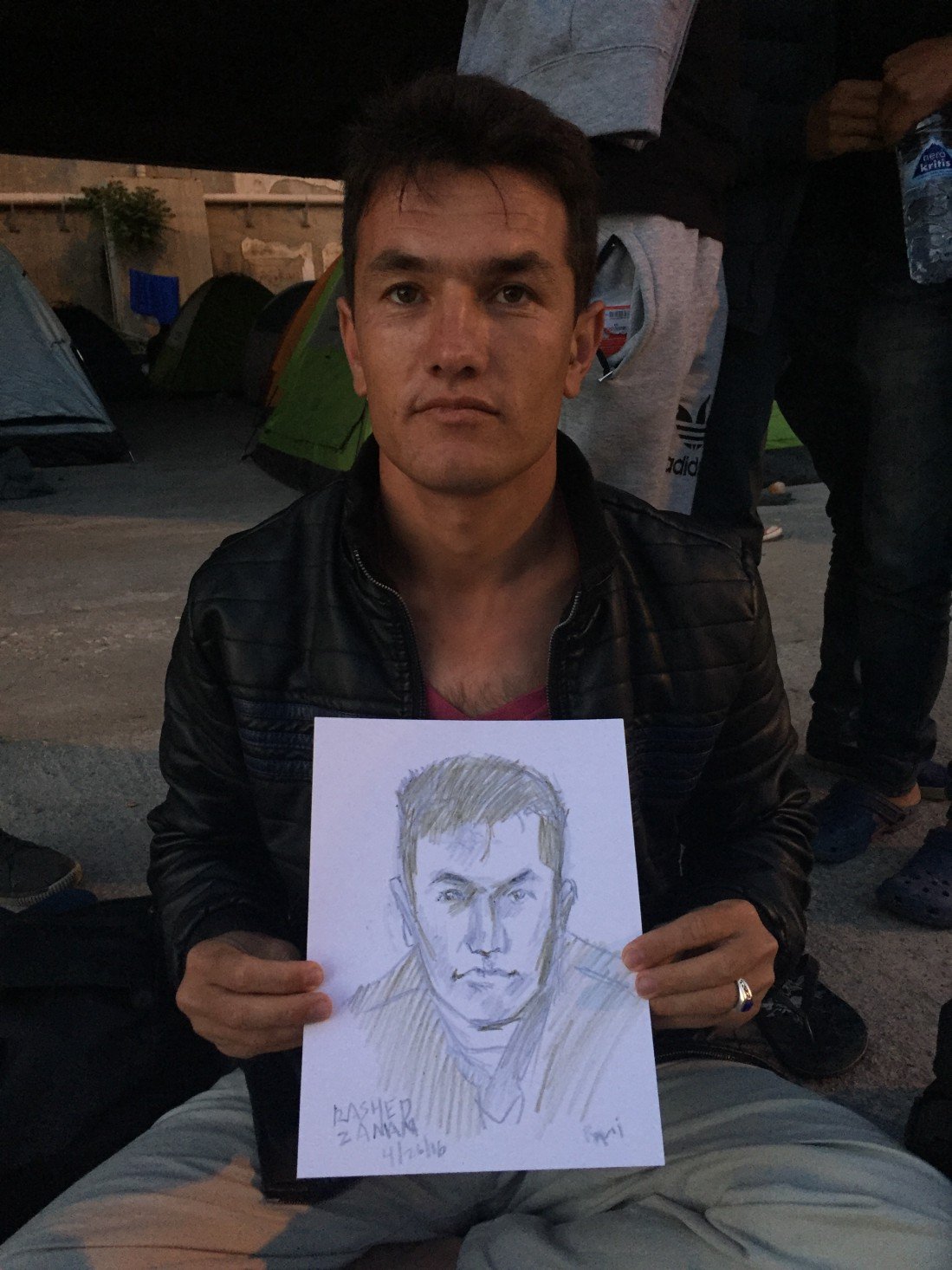

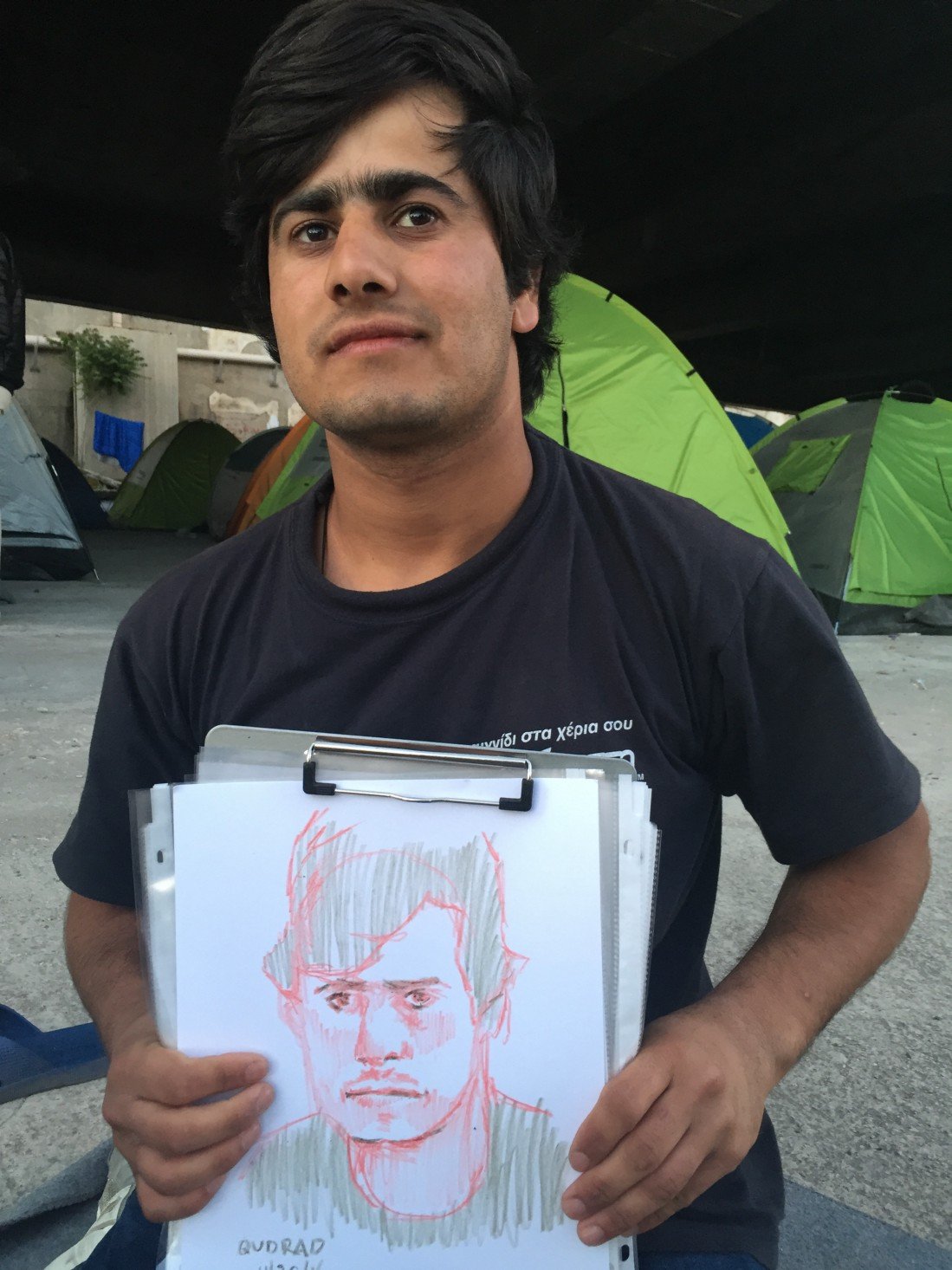

The sun began to set and a young boy circled the group with his eyes fixed on me and my bag. I motioned to him to sit by me and pulled out the crayons. That got the big boys’ attention and what followed was a draw-a-thon into the dark.

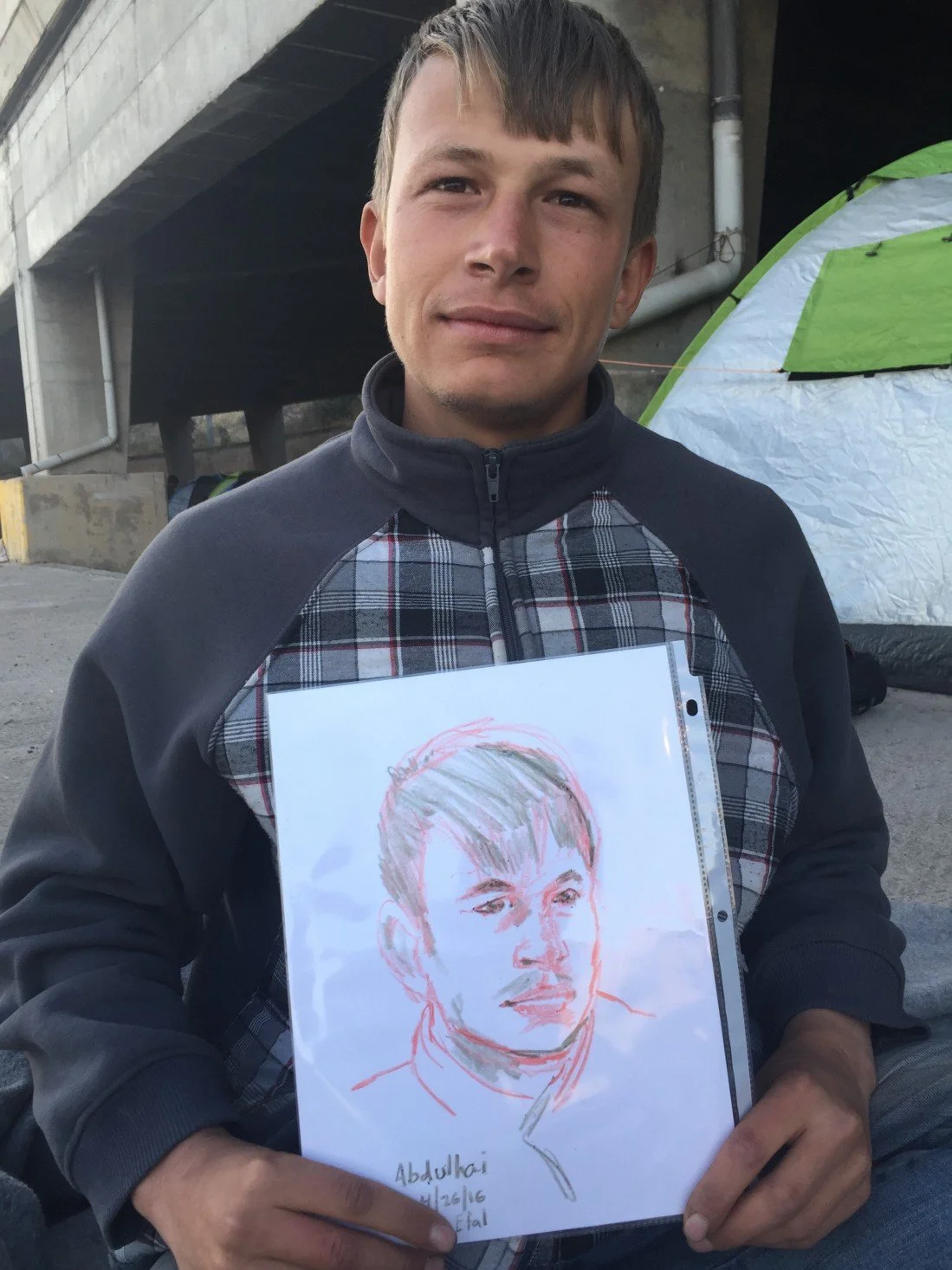

While drawing, as a matter of fact, Abdulhai told me he borrowed $6,000 to make the trip. He will need to pay that back some day. He came here all alone.

One grown man fixed his hair on his phone before sitting before me. Another seemed undecided on where to place his gaze. Another took long time choosing which colors to pull from the crayon box. Black was the most popular choice. Pink the most surprising. The machismo melted before my eyes and the big boys turned to little boys, appreciating being seen, acknowledged in silence.

I only had an hour in the camp before I had to begin my movement towards the airport. I told Masoud I had to leave and we both hugged. And hugged again. And photographed. And hugged again. I saw tears in his eyes and my heart began racing too, my body surging with care and sadness.

I left with Masoud my Timberland rolling duffle bag, sleeping bag and tent I used to sleep in South Dakota last summer surrounded by both the majestic Black Hills and spirits of the native Lakota people with whom this Afghan shares the vast sky and the desire to live.

I left the Afghan camp to search for Maher and his family. I wanted to say goodbye. Since I drew his deceased father and burned a hole in their tent rug, they have moved to another tent area in preparation to being relocated, again, to Skaramagas. I didn’t know where their tent moved to. It had been a couple of days since I saw them last, and when a young girl crossed my path I wan’t sure but thought it was his sister Amanda, or maybe “…Trea?” I asked her and she nodded no. […] She reached for my hand. She led me through to a small four-person tent. Bse their mother was combing Samil’s hair, Amanda and Trea were there too. I felt relieved and happy. Maher soon joined. I learned the one who led me to the tent looked like Trea because she was her cousin.

He invited me in, to eat, to drink, spend time. I felt torn. I wanted to comply, I also needed to make my way back, to shower, eat, get to the airport, fly back home to comfort and company and safety… and all the things I imagined they needed, too. I embraced Maher and the scope of the sadness and grief I have experienced in the camp finally opened.

I wanted to give hope. “Don’t make any promises you can’t fulfill,” A teaching I heard in the past reverbrated.

I said to Maher, “I visited Skaramagas — from outside. I heard from people there they have private lodging bathrooms, even electricity!”

Maher’s dark eyes glistened. “I don’t know what I can do, but please reach out for anything, you hear?” I asked Maher. “Thank you, brother.”

I walked away. In my throat — a lump the size of a four-person tent.

Crossing the nightlife streets of Piraeus, the bustling restaurants, the aromatic meats and beer, flat bread and mezze dishes. The Night Yasmin tree flowers scented the park with sweetness. At the small park across the main bus station, police tackled the Roma, Gypsy, camp.

I sat down at a restaurant by our apartment and ordered souvlaki, fries and a Mythos — the local beer and pride. I looked at my phone and ‘accepted’ all the friend requests from ‘Indiana Jones’ and the card-game hustlers from earlier that day. A post caught my eye from the “International Space Station” Facebook page that I followed. (“The ISS is a collaboration of 15 nations working together to create a world-class, state-of-the-art orbiting research facility. The Station is much more than a world-class laboratory; it is an international human experiment.”) A live feed interview with Taiwan-born and American-raised astronaut Dr. Kjell Lindgren, who returned from a mission, was about to begin. Le’haim.

My souvlaki arrived as I watched a man in blue NASA jumpsuit taking questions from the ‘comments’ line. “How did the space-grown lettuce taste?”(just like lettuce, and that’s a good thing.) “Do people snore in space?” (no, tissues obscure airways because of gravity. No gravity, no snoring.) “does space have a smell?” (not per se, materials exposed to space radiation have smell, like burnt metal.) I sipped my beer, recalled the smell of damp clothes and sweaty hair from the camp, and myself, and listened on.

“What’s the hardest day to day task while in space?”

DrKL “…it’s not a physical task but a mental one, to stay focused… one of my friends left a little note on our exercise device…’there is nothing more important than what you are doing right now’”.

I chewed on the grilled lamb and typed:

The announcer continued: “Casey here asks what’s it like to see the earth from the station?”

DrKL: “I remember the first view we had of the earth right after we launched has this brilliant white light coming through the window, and I was able to look back to the earth, and see that crescent, of our blue and white planet, was absolutely gorgeous…One particular night we were flying and the aurora was completely confluent, it was like we were flying through a sea of this hazy green fog that was undulating rapidly like a snake with highlights of red a and purple and it gave me goose bump. It is amazing to look down and see massive storms heading towards land, we saw the fires that were ravaging the north west of united states. You really feel for the people being affected by these events , gives you an odd connection with humanity in that respect. because you see the strength and beauty in some of these storms and you know things are pretty bad down on earth.”

I felt moved but grew tired and over-stimulated from the day. I contemplated asking for the check, not expecting to have my question answered. It was, by another’s:

“Having spent time in space and watching our beautiful planet, what simple message do you have for the people of earth as to how we might want to treat each-other?”

DrKL: “It’s a great question and there are two parts for that: the first part- we spend an inordinate time on the space station doing preventive and corrective maintenance to maintain this vehicle that’s protecting us in the cold void of space. This vehicle, that provides us water, food, protection from radiation and the harsh environments outside. When you look down at the earth, when you look through the Cupola [the ISS’ 7-window observatory] and you see the full face of the earth, you recognize that the Earth is a big beautiful but fragile space ship, hanging in the cold void of space, and it provides us food water, air to breath, protection from radiation and the cold void of space. We do not spend nearly the same amount of time taking care of Spaceship Earth as we do the International Space Station…”

The capsized cruise shuttle I saw earlier that day appeared in mind. The spaceman continued.

“…As crew members, on the ISS, we have to take care of each other, we have to take care of our spaceship, and I think that’s a lesson for those of us on Spaceship Earth.”

AFTERWORDS

“What did it feel like trying to walk on Earth after being out there so long?” Someone from the audience asks in the chat. The Astronaut answered:

“DrKL: It was pretty heavy. Gravity is what we grow up in, its what we know, but once you have been floating for five months or a year gravity is kind of a bummer. I felt heavy, I felt I had to work harder than normal to stand up and walk around in that non gravity environment, but the amazing thing is that the body adapts really quickly, the brain adapts really quickly, so within a couple of weeks I had my balance completely back and within a month I felt like I was almost 100%.”

A week since my return from Greece I have my balance ok and I am nearly adjusted to the new sense of gravity around me, of what I grew up in, what I know. At the airport, I took a Taxi and saw people living their life enjoying unimaginable liberties even in a country divided by values, races and classes. In every park I passed, my mind counted how many tents could fit there. At times sadness would settle, with a disconnect I heard from war veterans returning from war to meet the mundane, known, the gravity of life. I try not to pick at my emotions too much. They are tender. I enjoy the new buds on the trees, making omelets.

The spaceman taught me a new word, undulating. It is the waving, movement of things, of thoughts, of feelings, of peoples, of continents, of time, of helplessness, and of inspiration; it is the rippling line of children waiting for chai, of snaking unloading busses and confluent celestial lights of green red and purple tents, yellow stars and grey wool army blankets. It is the tide of knowing and not knowing, mourning and celebration, of plastic straw propellors launched from brown orphan hands and of orbiting aluminum spacecraft growing green moist leaves, of rolling of a cigarette, the offer to a stranger — and of the yearning to live.

Read the complete unedited blog posts from which the above is excerpted:

Day 1: Passover in Piraeus, (#1, 4/21/2016): Setting up

Day 2: Passover in Piraeus (#2, / 4/22/2016 ) : Kurdish Serenades, or How I burned a Yazidi Family’s Rug

Day 3: Passover in Piraeus (#3, 4/23/2016): Hanging in the in-Betweens

Day 4: Passover in Piraeus (#4, 4/24/16) : Friend Requests at Skaramagas

Day 5: Passover in Piraeus (#5, 4/25/2016): The Alif Ba of Serving Chai

Day 6: Passover in Piraeus (#6, 4/26/2016): Earth to Spaceman